Conquistador and scribe Francisco Martinez recorded the start of the 1566 expedition. “From the city of Santa Elena Captain Juan Pardo started on the first day of November in the year 1566, to penetrate into the interior to make it known and conquer it from here to Mexico . . .” The day that Martinez recorded as the start of the expedition was a month too early. The day Juan Pardo and his 150 conquistadors and unknown numbers of Native American porters set off from Fort San Felipe on Parris Island was on or near St. Andrews Day which is usually celebrated on the Sunday nearest November 30th. Martinez certainly meant December 1, 1566 when he recorded the first day of November.

Conquistador and scribe Francisco Martinez recorded the start of the 1566 expedition. “From the city of Santa Elena Captain Juan Pardo started on the first day of November in the year 1566, to penetrate into the interior to make it known and conquer it from here to Mexico . . .” The day that Martinez recorded as the start of the expedition was a month too early. The day Juan Pardo and his 150 conquistadors and unknown numbers of Native American porters set off from Fort San Felipe on Parris Island was on or near St. Andrews Day which is usually celebrated on the Sunday nearest November 30th. Martinez certainly meant December 1, 1566 when he recorded the first day of November. Nonetheless, 150 Spanish trekked into the Carolina wilderness. A 1578 report from Santa Elena indicates that ordinary soldiers in La Florida carried not only swords, daggers, and crossbows but early guns known as harquebuses with powder flasks and bullets. They wore quilted linen tunics known as escaupiles. These garments only marginally protected soldiers from arrows. The main reason they were chosen was because they were not as bulky or as uncomfortable to wear in hot weather as Spanish armor. No doubt, the men on Pardo’s expeditions were fitted in these garments and carried with them various armaments. In addition to extra boots and shoes, Pardo’s men also took along fiber sandals for comfort and practicality. Accompanying the Spaniards were large war dogs. These dogs had been trained to attack humans and were meant to be an intimidating presence to Native Americans who encountered them. Trade goods including beads, textiles, and axes were also carried along by the expedition. Although little could be spared, Pardo’s men carried small provisions of wine, cheese, and biscuits from Fort San Felipe’s dwindling stores.

Nonetheless, 150 Spanish trekked into the Carolina wilderness. A 1578 report from Santa Elena indicates that ordinary soldiers in La Florida carried not only swords, daggers, and crossbows but early guns known as harquebuses with powder flasks and bullets. They wore quilted linen tunics known as escaupiles. These garments only marginally protected soldiers from arrows. The main reason they were chosen was because they were not as bulky or as uncomfortable to wear in hot weather as Spanish armor. No doubt, the men on Pardo’s expeditions were fitted in these garments and carried with them various armaments. In addition to extra boots and shoes, Pardo’s men also took along fiber sandals for comfort and practicality. Accompanying the Spaniards were large war dogs. These dogs had been trained to attack humans and were meant to be an intimidating presence to Native Americans who encountered them. Trade goods including beads, textiles, and axes were also carried along by the expedition. Although little could be spared, Pardo’s men carried small provisions of wine, cheese, and biscuits from Fort San Felipe’s dwindling stores. Map from Walter Edgar's South Carolina: A History

Map from Walter Edgar's South Carolina: A HistoryIt must have been an odd site to the Native Americans as the Spaniards made their way from the coast in the bright sunshine and cool air of the winter of 1566. Loud and colorful with the red on white flags of the Burgundy Cross before them and their drums beating, they entered the unmapped frontier. On the second expedition in 1567 the scribe Bandera is told by Pardo that there is nothing to record of the villages forty leagues from Santa Elena because "the land is rough and full of swamps and Indians already subject and obedient" to the Spanish. However, we can follow the 1569 Bandera chronicle by the same scribe, whose notes from the 1566 expedition were reworked into a chronicle several years after this march, for the trip northward from Santa Elena. Their first stop, based on the assumption that Pardo followed the same trail on both his first and second expeditions (and we have no reason to think he did not) was the village of Uscamacu. Uscamacu sat on an island surrounded by rivers. It was “a sandy place of very good clay for cooking pots and tiles and other things that might be necessary.” Historian Charles Hudson who has extensively studied the routes of the Pardo expeditions believes that this village may have been located at the northern tip of St. Helena Island.

The march continued from here. Pardo proceeded north by northwest following a Native American trail near the Coosawhatchie River. He went in this direction rather than west toward New Spain because native guides probably told Pardo he could find sizable villages and supplies of food for his men. The next stop was the village of Ahoya. On his second expedition in 1567, Pardo would make an auto de fe or a Spanish act of faith in Ahoya. This was possibly a religious speech to the natives. It was noted that Ahoya was an island surrounded by rivers and suitable corn, grapes, and stocks. This village was probably located near Pocataligo or Yemassee. Next, Pardo’s men came upon a small village subject to Ahoya named Ahoyabe. It is placed by Hudson near today’s Cummings or even further north near Hampton. The trail now closely followed the black, oily flow of the Coosawhatchie River.

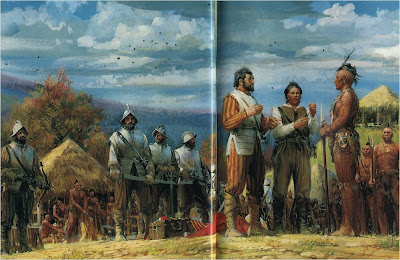

The march continued from here. Pardo proceeded north by northwest following a Native American trail near the Coosawhatchie River. He went in this direction rather than west toward New Spain because native guides probably told Pardo he could find sizable villages and supplies of food for his men. The next stop was the village of Ahoya. On his second expedition in 1567, Pardo would make an auto de fe or a Spanish act of faith in Ahoya. This was possibly a religious speech to the natives. It was noted that Ahoya was an island surrounded by rivers and suitable corn, grapes, and stocks. This village was probably located near Pocataligo or Yemassee. Next, Pardo’s men came upon a small village subject to Ahoya named Ahoyabe. It is placed by Hudson near today’s Cummings or even further north near Hampton. The trail now closely followed the black, oily flow of the Coosawhatchie River. Painting from National Geographic, March 1988

Painting from National Geographic, March 1988Eventually Pardo continued to march east and then turned north and west. He would in time make his way to the foot of the Appalachian Mountains. Along the way, following his orders for establishing the road to New Spain, he hastily built some forts and left small garrisons of men in each. At this point he received orders from Santa Elena to return immediately to help defend Fort San Felipe against the French. French corsairs had been sighted off the coast. So he retraced his route and in four months time he was right back where he had started on March 7, 1567. The French threat never materialized. Martinez, the Spanish soldier who recorded the first expedition wrote of the lands that he encountered that, “It is good in itself for bread and wine and all kinds of cattle raising because it is flat country with many rivers of fresh water and many groves where there are nuts and blackberries and medlars (persimmons) and liquid amber and many other kinds of groves. It is also a land for much hunting not only deer but hare and rabbit and birds and bear and lions (panthers).”

Pardo, known as the “valiant Captain from Asturias” set out with 120 men on his second expedition on September 1, 1567. He was to resupply and relieve the garrisons in the backcountry, and continue his quest for a path to New Spain. He followed the same path into the interior and then back as the first expedition. This time Pardo was ordered to have each chief he encountered to swear obedience to the Spanish king Phillip II and to Menendez in the presence of a notary and to agree to play tribute to the Spanish. Each major town had to build a storehouse to be stocked with maize, salt, and deer meat to supply the Spaniards on the coast. He distributed presents to Native American leaders along the way hoping to further bring them into amity with the Spaniards.

Pardo, known as the “valiant Captain from Asturias” set out with 120 men on his second expedition on September 1, 1567. He was to resupply and relieve the garrisons in the backcountry, and continue his quest for a path to New Spain. He followed the same path into the interior and then back as the first expedition. This time Pardo was ordered to have each chief he encountered to swear obedience to the Spanish king Phillip II and to Menendez in the presence of a notary and to agree to play tribute to the Spanish. Each major town had to build a storehouse to be stocked with maize, salt, and deer meat to supply the Spaniards on the coast. He distributed presents to Native American leaders along the way hoping to further bring them into amity with the Spaniards. Pardo supplied the small forts in the backcountry. The forts are never mentioned again. They probably became the casualty of attacks by Native Americans who destroyed them sometime very soon after Pardo’s last foray into this region. Pardo began to realize that the distance to New Spain was considerably more than anyone until that time had imagined. Realizing this, Pardo then began his trek home collecting as much foodstuffs as he could. He and his men foreswore corn and meat for other exotic Native American foods. They saved the corn for the men at Santa Elena and sent it ahead of them as they retraced their path to the coast. They ate deer meat, acorns, and roots supplied to them by the Indians. The Native Americans ate wild roots call batatas by the Spanish. It is known today as the American Groundnut and it is distinct but very similar to today’s sweet potatoes. At the large village of Cozoa, in accordance to Spanish wishes, the Native Americans had built a corncrib on posts high above the ground to protect it from pests and other animals. Pardo arrived there on February 16th and picked up 60 additional bushels of corn that were loaded into baskets and deerskins to be toted to the coast. Pardo and his men arrived back in Santa Elena on March 2, 1568. Only one man was lost in the two daring expeditions. The forts in the backcountry would disappear but it seems that Pardo’s leadership in unknown territory on the march was focused on the care of his men. To have only lost one man on these marches into unknown territory was a great achievement for this leader.

Pardo supplied the small forts in the backcountry. The forts are never mentioned again. They probably became the casualty of attacks by Native Americans who destroyed them sometime very soon after Pardo’s last foray into this region. Pardo began to realize that the distance to New Spain was considerably more than anyone until that time had imagined. Realizing this, Pardo then began his trek home collecting as much foodstuffs as he could. He and his men foreswore corn and meat for other exotic Native American foods. They saved the corn for the men at Santa Elena and sent it ahead of them as they retraced their path to the coast. They ate deer meat, acorns, and roots supplied to them by the Indians. The Native Americans ate wild roots call batatas by the Spanish. It is known today as the American Groundnut and it is distinct but very similar to today’s sweet potatoes. At the large village of Cozoa, in accordance to Spanish wishes, the Native Americans had built a corncrib on posts high above the ground to protect it from pests and other animals. Pardo arrived there on February 16th and picked up 60 additional bushels of corn that were loaded into baskets and deerskins to be toted to the coast. Pardo and his men arrived back in Santa Elena on March 2, 1568. Only one man was lost in the two daring expeditions. The forts in the backcountry would disappear but it seems that Pardo’s leadership in unknown territory on the march was focused on the care of his men. To have only lost one man on these marches into unknown territory was a great achievement for this leader. Painting from National Geographic, March 1988

Painting from National Geographic, March 1988Pardo returned to soldiering in the settlement of Santa Elena. In its heyday Santa Elena was a small farming community larger than St. Augustine. Corn, wheat, oats, pumpkins, chickpeans, beans, sugarcane and peaches were finally cultivated there with better agricultural practices. Cows, horses, pigs, sheep, and goats were raised. In 1576, however, Fort San Felipe was attacked by angry Native Americans and burned. It seems they had enough of Spanish conquistadors lording it over them. Although a subsequent fort was build, relations continued to be shaky with the Native Americans and the growth of the Spanish enclave at St. Augustine led Menendez and the Spanish to abandon Santa Elena in August 1587. The Spanish claims to the region would remain however until the 1670 settlement of the Carolina colony in a place that would become known as Charles Town. After that the frontier would tip into the hands of the English and for many the Spanish age would be forgotten.

Juan Pardo’s two expeditions had failed to forge a route to Mexico. However, these expeditions had accomplished many other things. They expanded the geographical knowledge of Europeans about North America. They also, through oaths, trade goods, and intimidation of the Native Americans solidified Spain’s claims to this region for many years to come. They relieved immediate pressure of starvation for the settlement at Santa Elena and established friendly relations with some Native Americans who lived in the interior. They also left for us a tantalizing, if incomplete record about the Native Americans and Spanish explorers interacting in the area that would one day be known as South Carolina.

Juan Pardo’s two expeditions had failed to forge a route to Mexico. However, these expeditions had accomplished many other things. They expanded the geographical knowledge of Europeans about North America. They also, through oaths, trade goods, and intimidation of the Native Americans solidified Spain’s claims to this region for many years to come. They relieved immediate pressure of starvation for the settlement at Santa Elena and established friendly relations with some Native Americans who lived in the interior. They also left for us a tantalizing, if incomplete record about the Native Americans and Spanish explorers interacting in the area that would one day be known as South Carolina.Andy Thomas

Works I consulted to write this blog:

Charles Hudson: The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Exploration of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568

Rowland, Moore, and Rogers: The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861

Lawrence S. Rowland: Window on the Atlantic: The Rise and Fall of Santa Elena, South Carolina's Spanish City

Charles Hudson: The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Exploration of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568

Rowland, Moore, and Rogers: The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861

Lawrence S. Rowland: Window on the Atlantic: The Rise and Fall of Santa Elena, South Carolina's Spanish City

Walter Edgar: South Carolina: A History

DePratter, Hudson, and Smith: Juan Pardo's Explorations in the Interior Southeast,1566-1568. The Florida Historical Quarterly 62:125-158, 1983

Paul Hoffman: A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast During the Sixteenth Century